To Infinity and Beyond

When I was 12, I watched Toy Story for the first time. Despite not understanding English, the movie's animations conveyed its message. Now, at 22, Toy Story remains a cherished part of my childhood. Somehow, I find myself watching the movie every six months.

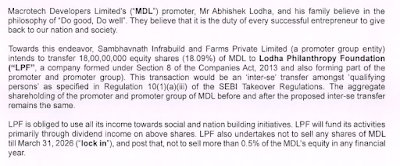

Curiosity about the Pixar logo alongside Disney's led us to research

Pixar. We discovered that Steve Jobs played a key role in managing Pixar and,

in 2006, became Disney's largest shareholder, earning billions despite being

ousted from Apple.

Just before his departure from Apple, Steve Jobs crossed paths with Ed

Catmull, who led the computer division at George Lucas's film studio. This

division specialized in hardware and software for creating digital images and

was home to a talented group of animators, including John Lasseter, an

executive with a deep passion for cartoons.

|

| Ed Catmull, Steve Jobs and John Lasseter (from left to right) |

In 1988, as Pixar faced financial struggles, Lasseter pitched an idea

for a short film called "Tin Toy." The story, inspired by classic

toys, followed a toy one-man band named Tinny and his comedic interactions with

a baby. Despite the company's tight finances, Jobs personally funded the

project, which went on to win an Oscar for Best Animated Short Film. This

victory established Pixar's reputation in animation.

Disney executives were impressed by "Tin Toy" and saw

potential in stories about toys with human-like emotions. While they attempted

to recruit Lasseter, his loyalty to Pixar and Jobs prevailed. Instead of

joining Disney, Lasseter remained committed to pioneering computer-generated

animation at Pixar.

Recognizing Pixar’s talent, Disney proposed a collaboration to produce a

feature film about toys. However, negotiations between Pixar and Disney were

complex. Jobs, still wary from his experiences at Apple, demanded a fair deal

that protected Pixar’s technology and granted the company shared rights to its

films.

In 1991, a deal was struck: Disney would own the film and its

characters, while Pixar would receive a share of ticket revenues and maintain

some creative input. This partnership led to the creation of "Toy

Story," a film that explored the inner lives of toys and their desire to

fulfill their purpose—being played with by children.

Toy Story was released on November 22, 1995 and opened to block buster commercial and critical success. It recouped its cost the first weekend, with a domestic opening of $30 million, and went on to become the top-grossing film of the year beating Batman Forever and Apollo 13, with $192 million in receipts domestically and a total of $362 million worldwide. According to the review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, 100% of the seventy-three critics surveyed gave it a positive review.

|

| click to enlarge |

The film's success prompted Jobs to renegotiate with Disney. He wanted

Pixar to be more than just a contractor; he envisioned it as a true animation

studio. Following a successful IPO that valued Pixar at over $1 billion, Jobs

secured a new deal with Disney, splitting costs and profits equally.

Under this deal, Pixar produced a string of successful films, including

"A Bug's Life," "Toy Story 2," and "Monsters,

Inc." However, a leaked email from Disney executives, which underestimated

the potential of "Finding Nemo," strained relations between the

companies. When "Finding Nemo" shattered box office records, Jobs

halted negotiations with Disney, leaving the future of their partnership

uncertain.

The turning point came with Bob Iger's appointment as Disney CEO.

Recognizing Pixar's value, Iger initiated discussions to acquire Pixar. The

$7.4 billion deal transformed Jobs into Disney’s largest shareholder and

positioned Pixar leaders John Lasseter and Ed Catmull at the helm of Disney

Animation.

The acquisition allowed Pixar to maintain its creative independence

while revitalizing Disney's animation division. Through this strategic move,

Steve Jobs not only secured Pixar's future but also contributed to Disney's

resurgence as a powerhouse in animation.

This remarkable journey led Jobs to hold 80% of his stock portfolio in

Disney shares at the time of his passing in 2011. Pixar's legacy of animated

classics, from "Toy Story" to "Up," continues to entertain

audiences worldwide.

Now, dear readers, what do you think? Would we have seen such beloved

animated movies if Steve Jobs hadn’t taken a chance on Pixar? Share your

thoughts in the comments below!

Comments

Post a Comment